Per noi, essere umani moderni, non è una novità vedere un dipinto con una tridimensionalità e una prospettiva quasi reali. Ma nel 1400 era una rivoluzione. La Trinità di Masaccio ha segnato il passaggio all'arte rinascimentale.

Ti piace la Trinità di Masaccio? |

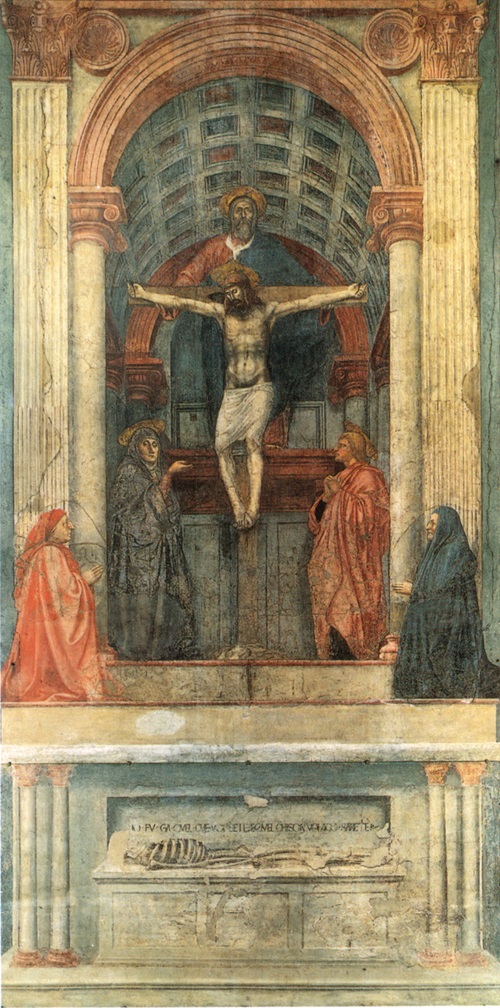

For us, modern human beings, it is nothing new to see a painting with a three-dimensionality and perspective that are almost real. But in the 1400s it was a revolution. The Trinity by Masaccio marked the transition to Renaissance art.

Do you like the Trinity by Masaccio? |

|---|

Trinità, dettaglio, Masaccio, 1427

(source Wikipedia)

Share this activity:

| Clicca sulle frasi sottolineate in verde nel testo seguente per ascoltare Franco che le pronuncia. |

Click on the sentences highlighted in green in the following text to listen to Franco pronouncing them. |

|---|---|

| "È accaduto tutto così velocemente" si disse Tommaso. "Forse troppo velocemente. Il gruppo degli artisti ufficiali non può amarmi... I miei pochi dipinti da ragazzo a Valdarno, poi a Firenze, a sedici anni, e l'iscrizione alla scuola d'arte come 'Masus S. Johannis Simonis pictor populi Santi Nicholai de Florentia'. Vivevo nel quartiere popolare della città ed ero ancora un ragazzo quando affrescai il chiostro della Chiesa del Carmine; abbastanza per procurarmi il lavoro alla cappella con Masolino. Eppure la cappella è mia perché vi si può vedere il mio famoso CHIAROSCURO. E la mia gente, vera, presa direttamente dalla vita fiorentina. Quei visi mi hanno aperto le porte di Firenze, con l'aiuto di Brunelleschi. | "It all happened so fast", Masaccio mused. "Perhaps too fast. The clique of official artists can't love me. Those few paintings as a boy in Valdarno. Then to Florence at 16. Inscribed in the art school as 'Masus S. Johannis Simonis pictor populi Santi Nicholai de Florentia.' Living in the popular quarters of the city I was still only a boy when I frescoed the cloister in the Carmine Church, enough to got me the job of doing the chapel with Masolino. Still, that chapel in mine. There they can see my CHIAROSCURO. And my real people straight out of Florentine life. Those faces opened the doors to Florence for me - with Brunelleschi’s help. |

Trinità, Masaccio, 1427

(source Wikipedia)

| Questa è la via attraverso cui sono arrivato alla mia CROCEFISSIONE. Finalmente un vero Cristo. Un uomo reale. Il petto gonfio. La testa abbassata fra le spalle, nel dolore e nella rassegnazione. Dicono tutti che questa sia l'espressione più alta della nuova arte. Il mio monumento. Ma forse, proprio per questo, per me è arrivato il momento di trasferirmi a Roma; ora che sono all'apice." | That's how I got to do my CRUCIFIXION. Now that is a real Christ. A real man. His chest swollen. His head down between his shoulders, in pain and resignation. They all say that this is the highest expression of our new art. My monument. Maybe it was time to move to Rome, while I’m on top." |

|---|---|

| Prudentemente,

Tommaso-Masaccio diede ancora un'occhiata ai suoi compagni

di viaggio e poi occhieggiò

a destra e a sinistra la desolata Via Cassia. Ondate di torce, lampade e fuochi donavano una luminosità giallastra al cielo di Roma, ora saldamente chiuso fra le sue mura di cinta. Tommaso, i pochi viaggiatori e i due loschi individui che avevano continuato fino all'URBE nonostante l'oscurità fosse caduta sulla collina romana, attendevano mentre un SEINEUR in un'elegante carrozza convinceva le guardie ad aprire le porte. Dentro le mura si fermarono, disorientati dai fuochi e dalle torce, dai cavalli, dalle mandrie e dall'attività frenetica. Dopo la campagna, la puzza delle vie strette nauseava Tommaso, il quale cercava la sua strada nel labirinto di passaggi e viuzze, circondato da oscure figure frettolose, e chiedeva indicazioni per arrivare a San Clemente. |

Tommaso-Masaccio

again eyed warily his travel companions, and cut his eyes

left and right along desolate parts of Via Cassia. Waves of torches and lamps and fires cast a yellow glow on the skies over Rome, now locked up tightly behind its great walls. Tommaso, the few wagoneers and those two dark figures who had continued on to the URBE even after darkness had fallen over the hill of Rome waited while a SEINEUR in an elegant carriage convinced the guards to open the gates. Inside the walls, they stopped, bewildered by the fires and torches, the horses and cattle and hectic activity. After the country side the stench of the narrow streets was nauseating to Tommaso, as he felt his way through the labyrinth of alleys and passageways surrounded by scurrying dark figures, following beckoning torches and occasional carriages hurrying through wider streets, and asking all the while directions to San Clemente. |

Ritratto di Masaccio di Nicolas de Larmessin, 1682

| Appena vide l'arena abbandonata seppe di essere vicino. "Ah, ecco la locanda dove siamo stati l'ultima volta" disse davanti a un locale sulla strada al quale avevano attaccato una torcia e dei rami davanti alla porta. Il calore e il fumo all'interno del locale erano terribili; l'odore era un misto di puzza e cibo cucinato. Le fiamme guizzavano e le ombre danzavano lungo gli spessi muri di pietra; dei personaggi andavano avanti e indietro bisbigliando commenti a quelli seduti mentre esaminavano i nuovi arrivati. "Io sicuramente non sembro ricco. Come se avessi dei soldi nella mia borsa! Ecco, laggiù, alla luce, vicino agli otri di vino è un buon posto. Ah, il vino bianco dei colli romani dopo il rosso fiorentino. E l'agnello alla romana, il pollo arrosto e il pane romano. Ah, ora è meglio. Questo vino va giù facilmente. Come acqua. Ma quei due fiorentini sono ancora qui," disse rendendosi conto all'improvviso dei due seduti al tavolo vicino. "Ah, rilassiamoci. Il vino è più forte di quello che sembra. Sta iniziando ad andarmi alla testa. Forse la zuppa era guasta. Sento lo stomaco strano. Il vino mi è andato alla testa. Ho bisogno d'aria. Aria o svengo. Lasciatemi, qui un momento, aria, torno subito, io, no, ...no, non ho finito il mio lavoro... c'è tanto... San Clemente... e..." | When he saw the abandoned arena he knew he was close. "Ah, there is the Inn where we stayed last time," he said, outside a groundfloor establishment with a torch and branches hanging over its door. The heat and the smoke inside was shocking, the smells a mixture of stink and cooking food. Flames flickered and shadows danced along thick stone walls, figures darted in and out, whispered exchanges among those seated as they examined new arrivals. "I certainly can't look rich. As I had some think money bag! There, the place in the light near the wine kegs is good. Ah, the white wine from the Roman hills is good after Florentine reds. And Roman style lamb and roasted chicken and Roman bread. Ah, that’s better now. This wine goes down easy. Like water. But those two Florentines here too," he said, suddenly aware of them at the next table. "Ah relax. The wine is stronger than it seems. It's beginning to go to my head. Eat some more chicken. Maybe that soup was spoiled. My stomach feels strange. That wine has already hit me. Need air. Air or I'll pass out. Let me, here a moment, need air, I’ll be right back, I’ll, no, ... no… I haven’t finished my work…there’s much… San Clementee… and…" |

|---|---|

| Nell'anno 1429 il nome del pittore del popolo, Masaccio, fu cancellato dagli archivi del territorio di Firenze con una nota: "secondo quanto si dice, morto a Roma". Quell'anno, oppure il 1428. Nessuno lo sa con certezza. Una morte misteriosa quella del pittore-genio, di 27 anni, che cambiò la direzione della pittura fiorentina e preparò il territorio per il rinascimento dell'arte europea. Dal suo primo polittico nella chiesa di San Giovenale a Cascia-Reggello, vicino a Firenze, a una delle meraviglie dell'arte fiorentina, gli affreschi della cappella Brancacci nella chiesa del Carmine a San Frediano, un quartiere di Firenze. Ogni galleria con un lavoro di Masaccio lo protegge gelosamente: gli Uffizi di Firenze, la Galleria Capodimonte di Napoli, il Museo Nazionale di Pisa, La Galleria Nazionale di Londra, il Museo Staatliche di Berlino, il Lanckoranski a Vienna; alcuni lavori attribuiti a Masaccio sono a San Clemente e un trittico a Santa Maria Maggiore a Roma. | In the year 1429 the name of the people's painter Masaccio was cancelled from the landed property records of Florence with the remark: 'reputedly died in Rome.' Either that year or 1428. No one is certain. A mysterious death, that of the painter-genius, of 27 years old, who changed the direction of Florentine painting and prepared the ground for the Renaissance of European art. From his early polyptich in the Church of San Giovenale in Cascia-Reggello near Florence to one of the highlights of Florentine art - his frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel in the Church of Carmine in the San Frediano district of Florence. Any gallery with a Masaccio work guards it jealously: the Uffizi in Florence, the Capodimonte Gallery in Naples, the National Museum of Pisa, the National Gallery in London, the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, the Lanckoranski in Vienna; some works attributed to Massaccio in San Clemente and a tryptich in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. |

Trittico di San Giovenale, dettaglio, Masaccio, 1422

| Masaccio fu ammirato dai contemporanei e da generazioni di pittori fiorentini, da Paolo Uccello a Piero della Francesca e Leonardo da Vinci, da Michelangelo a Raffaello e dal più importante biografo dell'arte rinascimentale: Vasari. Tutti ammirati dell'innovatore e modernista Masaccio, il "pittore fondamentale per il Rinascimento", immortalato dal commento sintetico del suo amico e compagno di innovazioni, l'architetto Brunelleschi, alla notizia della sua morte: "Noi habbiamo fatto una gran perdita". | Admired by contemporaries and generations of Florentine painters from Paolo Uccello to Piero della Francesca and Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raffaello, and the most important biographer of Renaissance art, Vasari. All in awe of the innovator and modernist Masaccio the "fundamental painter of the Renaissance," immortalized by that synthetic comment of his friend and follow innovator the architect Brunelleschi, about the death of his young friend: "Noi habbiamo fatto una gran perdita" (We have had a great loss.) |

|---|---|

Masaccio partì per Roma nel 1428 o 1429 e sparì. Avvelenato dai rivali? Ucciso dai banditi lungo il viaggio o per le strade di Roma? Nessuno lo sa. Egli fu inghiottito da un mondo dinamico e in transizione: dalle antiche superstizioni al realismo e all'umanesimo. Un genio e un ribelle, era temuto e odiato da politici intriganti e da artisti in competizione con lui.

|

Masaccio left for Rome in 1428 or 1429 and disappeared. Poisoned by rivals? Killed by bandits along the way or in the alleys of Rome? No one knows. He was swallowed up by a dynamic world, in change from a world ruled by ancient superstitions to one of realism and even humanism. A genius and a rebel, he was feared and hated by intriguing politicians and by artist competitors.

|

| Nota sull'autore:

Gaither Stewart vive a Roma e collabora, fra diversi progetti, come corrispondente dall'Europa per il Greanville Post. Esperto giornalista, romanziere e saggista tratta diversi argomenti, dalla cultura alla storia alla politica. È anche l'autore della Trilogia Europea, celebrati racconti di spie di cui l'ultimo volume, Time of Exile, è stato recentemente pubblicato da Punto Press. |

Note about the author:

Gaither Stewart is based in Rome and serves—inter alia—as European correspondent for The Greanville Post. A veteran journalist, novelist, and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press. |

Advanced Lesson 2

Lesson Tools:

References:

Navigation: